PowerWash Simulator, initially launched into Early Access in 2021 and declared Finished the next year, is a game of long-form Zen, where players navigate around a job site in first person, firing their pressurized water nozzles at dirt-encrusted buildings, vehicles, and assorted other things. It is through the magic of texture-masking and some very nice shader programming that players get the full experience of power-washing, whether they wish to methodically sweep back and forth in a slow scanning movement, or decide to draw happy faces in the grime; the exact locations of where the hose is spraying are indicated in the dirt. Great effort is taken to make the washing process look as real as possible, even if the actual materials being washed are, at times, anything but realistic. The game eventually culminates in the player hosing down ancient statues, UFOs, and an entire off-shore temple, solving an absurd time-travel plot involving a James Bond-esque mad scientist and averting volcanic apocalypse, a plotline that largely takes place in the background until its denouement.

Low-key absurdity notwithstanding, PowerWash exemplifies what I would call the “chore game”: a gamified simulation of an every-day task. Other notable games like House Flipper, Leaf Blower Co., WW2 Rebuilder, and Fresh Start Cleaning Simulator, fill out the bulk of their play time by tasking the player with a long, sometimes tedious clean-up task, and letting the player decide how to divide it up. For the most part, these games are deadly serious, only developing mild quirks over time as they are augmented with tie-in DLC or ill-advised support for user generated add-ons (or just allowances for the player to be an utter goofball). Maybe there are occasional lawn gnomes or cats to interact with, or inexplicable medieval peasants or Dark Souls bonfires in their respective base games, but any outward appearance of seriousness goes out the window once they introduce, say, Final Fantasy 7, SpongeBob SquarePants, or Warhammer 40K-themed missions for the player to spray, scrub, or interior-redecorate.

Which leads me to wonder why a lot of these games even bother putting up a front about it in the first place. Surely we, the gaming public, wouldn’t mind a silly game about being a robot vacuum cleaner, mopping up salt circles and pentagram-shaped ash stains in the rugs of a haunted mansion. In a few cases, that’s even the direct sales pitch. Perhaps it’s out of a worry that the absurdity of a game’s concept is but one single joke, and once the joke has stopped being funny, the rest of the game may not hold up. At least a few games may choose to compensate by keeping the jokes rolling, even at the potential expense of loading themselves up with more duds than bangers, with the vain hope that the sheer volume and disposability of said jokes means that a misfire won’t hurt the experience that badly. Said games have a habit of never, ever shutting up, either. (Hello, High On Life, Borderlands 2, Sunset Overdrive…)

But all of that leans heavily on the idea that a joke is something that must be told, rather than witnessed, or simply experienced. A joke does not need to be a story, a line of dialogue, or even an event. Silliness and absurdity do not need to be tied to a timeline. They can be sewn into the very fabric of the game, into the world, with such subtlety that the player comes to accept it as utter normality. They can even serve to mask other absurdities. Only upon stepping back and attempting to explain it does the player have their light-bulb moment, and ask themselves, “what in the hell am I doing?”

It is this tool that Chibi-Robo wields, most of all.

Spread across five different games over a ten-year span, the Chibi-Robo series is, at its simplest explanation, a “chore game.” Your task is to pick up trash, scrub stains, vacuum dust, tend to gardens, and otherwise help the residents of your house. The biggest catch, of course, is that you are three inches tall, and running on a battery that needs recharging roughly every two minutes. Fortunately, your charging plug is permanently hard-wired to your posterior, so you can easily plug yourself in and continue your task in seconds. In the process of cleansing the household, Chibi can ransack various cabinets, drawers, and couch cushions for Moolah (a currency with an appropriately funky M symbol), which can be spent on plenty of other things, useful or otherwise. Chibi-Robo truly spares no scrap of privacy, leaves no cushion unturned, no drawer unopened, in pursuit of making the household sparkle, and squeezing Happiness out of every sentient (or perhaps imaginarily sentient) being. Wandering around a giant house (or among blades of grass as tall as skyscrapers) is a wonderful demonstration of forced perspective in video games, that even in 2005, I was more accustomed to seeing in first-person shooter mods. As fun as it was sniping at my older sibling from the top of a bookcase in SiN, Half-Life, or World of Padman, I’d always felt that Being Tiny could carry an entire game.

Were mere Tininess the only quirk it had to offer, though, Chibi-Robo would be no different from the laundry list of chore games I’d mentioned earlier. But what it offers on top of this is whimsy in spades. Your owners in the first game, the humans who decided to purchase you in the first place at great personal expense, consist of an overworked house wife who is nearing her breaking point with her lout of a husband, said husband who is dedicated to all things tokusatsu, and their little daughter Jenny, who believes that she is a frog. Also present is a dog named Tao, designer Kenichi Nishi’s real-world pet who also appeared in his directorial debut, Moon: Remix RPG Adventure, among other games. All of them have their own needs and wants, and ways they’ll help (or interfere unwittingly) with Chibi’s daily tasks; Tao, for example, leaves muddy footprints everywhere that will need scrubbing (with Dad’s discarded superhero toothbrush). When speaking to your humans, they will tend to pick Chibi up and hold it in front of them, which is simultaneously adorable and frightening, like watching someone scooping up a baby rabbit out of the pen without fully supporting it (oh my God, please don’t drop it!).

Once the humans (and dog) have gone to bed, the house should, by all rights, be nice and quiet. Except the Toy Story rule is in effect in Chibi-Robo: when the people aren’t around, toys come alive. Stuffed animals, action figures, dog chew toys, that creepy sarcophagus under the bed(?!), even the rubber shark in the kitchen sink: all have their own personalities, relationships, and needs, just like their daylight caretakers. Chibi appeases their whims just as it would those of the humans, like covertly delivering love letters from the stuffed centipede to the Space Detective Drake Redcrest action figure (who is quite oblivious to them). There are always goals to meet, characters to consult, and mysteries to solve, even if those mysteries amount to “why are there pirates in the basement?” and “why are these eggs shooting at me?”

The day-to-day action of Chibi-Robo hinges a lot on Chibi’s own ever-increasing capabilities. With only a miniscule 60 Watt battery (yes, it really should be milliamp-hours), Chibi will find itself needing to plug in and recharge very frequently; some trips around the house may very nearly exhaust that supply, especially through rooms that do not have accessible power outlets (especially a problem in the third game, where they may be unreachable or even broken). By performing tasks, like cleaning trash and bringing items to their owners (like Jenny’s collection of frog rings), Chibi earns Happy Points, which are tallied at the end of every day-night cycle. Meeting certain milestones earns upgrades, such as battery expansions, tools, even costumes with special functions.

Actually getting your chores done entails some outside-the-box thinking, in different ways depending on the game. While basic locomotion does not change (opening drawers to form crude staircases, climbing chair legs and curtains to reach high places), Chibi’s tools are quite different from game to game. While a toothbrush and a water-squirter are pretty well a given, Chibi may also be equipped with a boom box (that must be manually spun with the stylus to encourage flowers to dance), a radar, a blaster, or a police uniform, complete with blank-firing pistol (for scaring off rodents). Chibi may also collect upgrade chips to teach it to swing its own charging cable around, both for use as a grappling hook and for self-defense against ghosts. The shrunken perspective means these tools may also need to serve you towards accomplishing tasks that would not otherwise be difficult for a normal-sized person. Cleaning the kitchen table may mean scurrying up a chair leg, followed by tossing your plug at the power outlet, and using your cable to get up the rest of the way. Climbing the stairs in the foyer is a journey that may require half the game to properly prepare for, as it is quite taxing on Chibi’s battery, on top of the occasional need to zip over short gaps with the also-power-hungry Chibi-Copter. (To say nothing of what you’ll have to do once you’re at the top.)

All of this is scored to the most deliberately Mickey Mouse soundtrack that a GameCube (or a DS) could output. The actual game music is wonderfully quirky and experimental, perhaps a little unhinged here and there, but the true attraction audio-wise is the accompanying sound. Every step Chibi takes is punctuated by a tap on pizzicato string, or perhaps on a xylophone, depending on the surface on which it is running. Rising woodwinds highlight long (and sometimes dangerous) climbs up lamp stands or windowshade pulls. Most of the cleaning tools sound like strums of guitar (the infectious toothbrush tune remains lodged in my psyche to this day), and even the radar locator comes with a cheesy toy-keyboard beat that gets progressively funkier as you approach a signature. It was this approach to sound design that helped me to remember that Chibi-Robo existed, even years after it had originally released; it was the first thing I’d noticed about it when playing a demo of it at an in-store kiosk. If the designers at Skip deserved an award for anything, it’d be abandoning all expectations of realistic sound design and striking their own path.

Another way Chibi-Robo stands out in audio, is voices. While all of the talking in the series is done via text, characters still audibly speak, but what comes out of their mouths is not necessarily language. This is something of a developer trademark; as far back as the Love-di-Lic days of Moon and UFO: A Day in the Life, every speaking character has a distinct library of babbles that play back as their words appear on the screen. These are generally chopped up bits of actual sentences, often distorted or pitched up or down beyond comprehension, and fired off at a fast enough rate that the player simply cannot hang on to any word. Keen listeners may pick up the odd fragment or two; young Jenny speaks in frog-like “gero-geros” (unless you are a frog yourself, then her speech becomes “translated”), while the egg-soldiers in the foyer pipe up in bits of “yessirs.”

I speak of these things - the sound, the concept, the whimsy - as if they are unchanging facts across the entirety of the Chibi-Robo series. This is true of the first three games, at least; even with Park Patrol taking a conceptual swerve into tending flowers in a city park instead of cleaning a house, the whimsy is there to carry it the rest of the way. This, unfortunately, changed with the last two games, both for Nintendo 3DS, and both attempting even more wild swerves on the formula.

2013 brought us Photo Finder (Let's Go Photo!), in which the 3D exploration takes a back seat to an augmented reality gimmick. Chibi spends its Happy Points (which accrue much slower than before) on sheets of film for a digitizing camera. Each film is designed to capture a specific shape; the player must find the real object depicted and take a good, clear photograph of it using the 3DS camera. Unfortunately, because the 3DS camera is not very good (it is a pair of 320x240 webcams, essentially, with noisy sensors and poor light intake), capturing your subjects requires a lot of premeditation. The objects must be placed against a clear background that helps them stand out, in strong lighting, so that the game's edge detection algorithm can correctly separate it from its surroundings. In practice this means having a convenient green screen in direct sunlight, otherwise you are going to be wasting your film with feeble attempts at stage lighting. I have attempted this indoors with flashlights and note cards. It does not work.

Compounding this frustration is the fact that the film is not just disposable, but expensive; the early film shapes cost 30 happies, which are earned easily enough, with missions and mini games that provide ample rewards in early game. Once those are exhausted, though, all you can do is warp back to their given zones (you don't get free roam of a house, only little vignettes of kitchen counters or desktops) and pick up candy wrappers to grind a few points each time. The zones don't have power outlets, either, and your battery is frustratingly small. Sucking up the same little patches of dust for a mere 4 Happy Points each run becomes an agonizing grind to save up the 30 to 50 you’d need to replace a botched film. Photo Finder did at some point have an online community challenge component, but this part of the game shut down only one year after release, in 2014. I have no idea how it would have worked, or whether it would have alleviated the grind; I did not come to purchase Photo Finder until 2016.

The grind is not Photo Finder’s only problem. While the distinctive babbling is still present (your manager, Telly - in his new iPhone-esque form factor - has gone back to sounding just like he did in the GameCube game), Photo Finder’s soundtrack has gone into a weirdly ethereal, almost vaporwave-ish feel. It abandons all whimsy, and sounds like something you’d hear in an abandoned shopping mall. Chibi does not walk to its own tune anymore, either, as all of the musical stabs have been replaced with more realistic little clinks and taps, making Chibi sound quite hollow and lifeless. (I mean, it is a robot, but still.) Even the act of recharging, normally accompanied by jauntily rising woodwinds and ostentatious bell chimes, now comes with a single rising synth note, and a very Corporate-Approved “dong” sound.

The environments are devoid of wacky characters aside from a small handful of toys; it’s unclear who even lives in these places. Drake Redcrest is back, but all he does is complain about how the world is at Peace and there is no Evil to Fight. A retro wind-up robot toy asks you nonsensical trivia questions, and doles out a meager helping of Happy Points if you answer correctly. There are new Chibi-Tots, even tinier versions of Chibi-Robo, hiding in random places, but they, too, just give you a couple of Happy Points and encourage you to find them again. They don’t have stories or wants. They’re just kind of… there.

All of this comes with the most foul of cherries on top: technical drawbacks. Beyond the edge-detection algorithm barely working and the 3DS’s cameras being a poor fit to the task, Photo Finder just runs badly. Maybe the graphics engine has stronger capabilities compared to even the GameCube game (though, admittedly, that game was not exactly winning Best Graphics awards even at the time), with nice chrome effects and a tilt-shift effect to really sell the smallness of your perspective, but the game inexplicably runs at only 15 frames per second while exploring, making the entire thing feel sluggish, even if it does look great in screenshots.

It is, perhaps, the failure of Chibi-Robo Photo Finder that prompted a desire by Nintendo to reinvent the series. Two years later, in 2015, came the release of Chibi-Robo: Zip-Lash, a title that completely threw out all previous gameplay conventions to start completely anew. This time around, our Chibi is tasked not with cleaning a house, maintaining a park, or filling a museum, but Saving The World. It turns out all of Earth’s Resources are being stolen away by Aliens, and it is up to Chibi to send them packing, so they’ll leave our planet alone. There are no humans to help, and only token trash items to pick up; the bulk of the game is now side-view platforming, and Chibi now fights exclusively by flinging its plug around. To be honest, this does make Zip-Lash feel like an off-brand Kirby game, and I’m unsure why the sudden change.

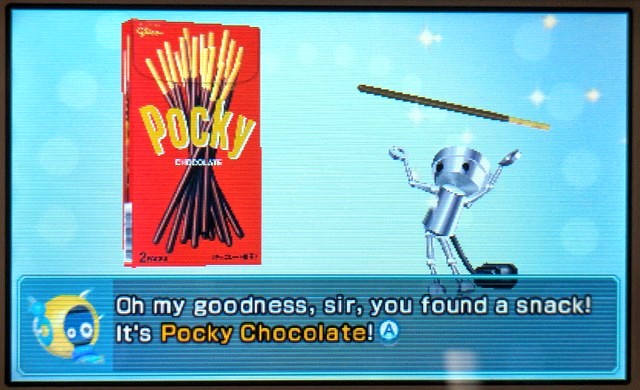

Even weirder is the sudden appearance of real-world snack food products as collectible treasures. The aliens aren’t content with stealing entire cargo ships and oil silos; they’re apparently stealing the world’s supply of candies, chocolates, and potato chips, too. You find them tucked away in secret areas, in treasure chests, and the game gives over-the-top fanfare to your collection of Pocky sticks and packs of Mentos. Not just finding them, either; you’ll run into toys once in a while that will happily sing the praises of each snack food’s flavor, while doing aerobatics across the screen. It’s quite a lot of hooberbloob for breath mints, especially compared to the entire rest of the game.

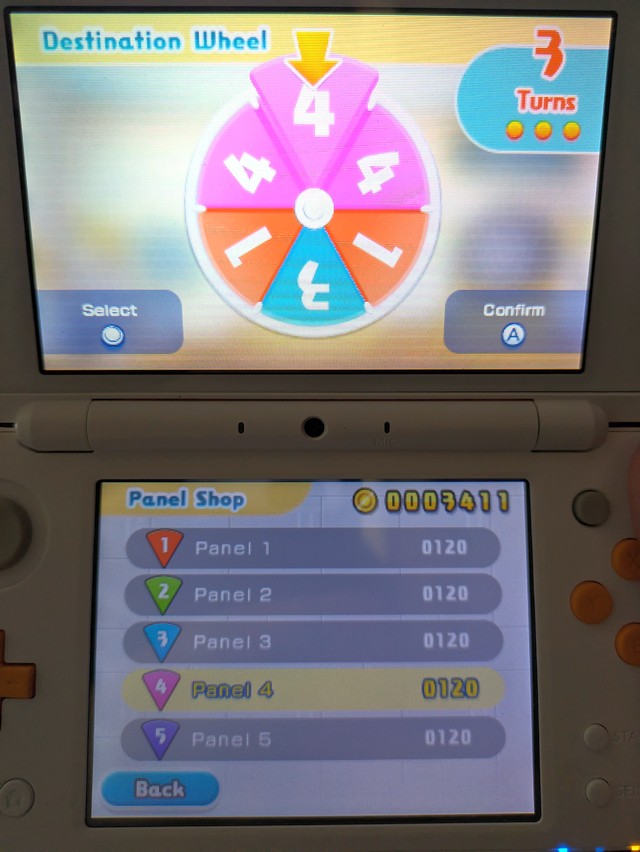

All this sounds like small potatoes; it really is at least a functional game, if not a particularly imaginative one anymore, if not for the real kicker that is the stage select spinner. Upon finishing a stage, you are shown the Destination Wheel, a Wheel of Fortune-esque spinner divided into six numbered panels. Your next stage is determined by which number the wheel lands on. There are ways to rig this spinner; hitting the gold or silver UFO at the end of the stage gives you opportunities to spin the wheel again if you don’t like the result, or you can spend coins (not Moolah anymore) to buy new panels to place on the wheel wherever you like. You are likely to be sitting on a huge pile of coins by the time it becomes necessary to rig the wheel, unless you lean on the assist items a lot (the only other thing coins can be spent on), but if you can’t re-spin, and didn’t think to buy new panels, it’s possible to land on a stage you’ve already completed. And when that happens, you have to play that stage again, no matter what.

Really, I feel that such repetition is the heart of why Zip-Lash is so unsatisfying. Between the occasional flub on the Wheel, and the fact that it is impossible to 100% clear a level on the first try (some collectibles cannot appear until a replay), it is clear that Zip-Lash is a game that wants you to play it over and over. It continually throws you into levels that tend to look the same, asks you to solve puzzles that tend to feel the same, and tops it all off by encouraging you to go back to those levels over and over to find that last hidden candy bar, unlock that costume, or rescue that last Chibi-Tot. And do it all without taking damage or using items. Which wouldn’t be such a big deal, if the stages had much variety among themselves, but with a handful of exceptions, one stage may as well be as good as another. It’s no wonder that I, and the handful of other people I’ve spoken to about the game, largely gave up within the first World.

To think that if Nintendo and Skip had waited another few years, they’d have witnessed the meteoric rise of the Chore Game. Maybe they would have seen the kind of market in which a traditional-style Chibi-Robo game could succeed.

Which isn’t to say that Chibi-Robo is over and done, never to be seen again. The launch of the Nintendo Switch 2 (a device vastly out of my reach and budget) brought with it a new selection of downloadable GameCube games, accessible to their Switch Online subscribers. Among these games is the original Chibi-Robo. Granted, I see few people talking about it in 2025, compared to the number of rants I saw about “why did they add Bubsy?” But I’d chalk that up to there not being a ton of Subscribers in my circles, let alone a ton of people that own Switch 2 consoles. But depending on how Nintendo derives their player figures for these things, I have to wonder if they’d give little Chibi another chance.

At the same time, though, we don’t need Nintendo to be playing ball. We live in the 2020s; it’s an era full of Spiritual Successors, both by original devs sans licenses, and by the True Fans of the games gone by. To that end, a studio calling themselves “Tiny Wonder” successfully raised a little over $180,000 to fund a new game titled koROBO. It does outwardly resemble Chibi-Robo, and in fact, the project is directed by Skip veterans Kenichi Nishi, Hiroshi Moriyama, and Keita Eto, along with other key members of the old Chibi-Robo dev team. Maybe this will bring back some of that spark, that whimsy. I’m certainly interested in seeing where they go with it, even if it will probably be ages before they’ve finished, and yet more before I can afford to pay them money for it.

But you know? I haven’t fully finished the old ones. The really old ones. God, those games are, like, 15-20 years old now.