The Digital Golf Swing

The swing of a golf club is a remarkably complex thing.

What might first appear to be nothing more than hitting a ball, very hard, with a weighted stick, has a lot of complicated factors that go into it. The very form and motion of the swing is affected by the individual movements of the golfer's hands, wrists, forearms, shoulders, spine, hips, knees, feet. The air resistance of the club head. The weight and balance. The hardness or softness of the ground, beneath the ball, beneath the feet. Minute details of the golfer's stance, how far they've bent over, where their feet are at in relation to each other and the slope of the ball's lie. There is so much going on here that there are scientists whose life's work is to study the golf swing, like the late Alastair Cochran, a nuclear physics Ph.D whose work went into the book, "Search for the Perfect Swing."

|

| Professional golfer Gary Player, imitating Arnold Palmer's golf swing on The Ed Sullivan Show 🎥 in 1965. |

Video games are remarkably complex things.

The majority of video games manage to condense complicated things - like physics, acrobatic maneuvers, athletic feats, combat, technical skills - into a package that an average player can interact with, often without prior knowledge. Many video game players admit that the reason they play is because video games enable people to do things they’d never do in reality, thus, lending to the broad appeal of the medium overall. Maybe any given American can learn to play golf in the real world, given the time and opportunity, but speaking from personal experience, maybe not. A lot of us may find ourselves whiffing the ball entirely, if not gouging a sizable divot in the fairway (assuming our ball lands there in the first place). Getting the ball to go where we want is only half of the problem; getting the club to go where we want is a much greater issue to contend with first. A golfer like me would never dream of finishing under par on anything but the simplest of miniature links. It is for players like myself that video games exhibit their broad appeal. I, the clumsiest of club-wielders, can dial in the perfect fairway drive in just three clicks of a mouse. Or a flick of a thumbstick. Or a strong shove on an oversized trackball.

|

| 18 Holes Pro Golf, Data East, 1981, arcade. The swing meter - and the golfer's backswing - automatically move back and forth; the player needs only press one button at the proper time to hit the ball. |

So much of what makes sports so entertaining relies on the skills and training of the athletes, who have spent so much of their lives developing exacting control over their muscles, tuning their action and reaction into the most optimal behaviors to their sport of choice. The baseball pitcher knows instinctively how the individual fingers on their hand need to move, to impart a spin on the ball as it leaves their grip. The football quarterback understands the importance of their own center of gravity, to remain upright when faced with thousands of pounds of opposing team coming at them. The tennis ace is able to predict where the ball will be, between now and a mere fraction of a second later, and position themselves precisely in 3D space to make contact with it, and the exact angling of their racquet to cause the ball to curve. The golfer understands potential and kinetic energy, windage, elevation, and the point of impact, in relation to how their tiny ball will fly, bounce, roll, and hopefully stop where they expect it to.

|

| Visual-calculus of Rory McIlroy's 351 yard drive from the Genesis Invitational, from a compilation of long drives 🎥 on the PGA Tour's official YouTube channel. |

Video game sports seek to tackle a uniquely compelling problem, of not just how to simplify all of these aspects of athleticism for an interface that (most of the time) requires no athletics whatsoever, but which elements to simplify. In a baseball game, the pitcher may need to press a button and a direction together to determine which direction the ball should go, or at times, the desired pitch is simply chosen from a menu, or using a different button (so the other player can't see which one they've chosen). Whether the virtual football player can continue charging down the field after being tackled by three other players may be nothing more than some internal statistics values, flashing numbers back and forth, but it may also depend on the player pressing an action button with speed or timing to counteract a poor outcome. The tennis game may display an on-screen indicator of where the ball will bounce, and the swing of the racquet is the simple press of a button (or two buttons, if the game is sufficiently ambitious), or it may use a form of motion or pressure control for extra precision.

The golf simulator, then, can be simplified in its swing system. Many factors of the swing may be simulated under the hood, or else the engine can simply ignore them. Most commonly, a golf game will handle swinging with a large button that says "SWING." Clicking once on this button will start the rise of a swing meter, and the button must be clicked again at the desired level of swing power. Often times, a third click is also needed at the bottom of the swing meter, representing the point of impact on the ball, affecting hook, slice, or even top or back spin. The primary difficulty in the game, then, is for the player to intuit the necessary amount of swing power, then correctly time both button presses, to strike the ball with the desired strength and accuracy. This is what is known as a 3-click swing, and it is seen in the vast majority of golf simulators throughout gaming history.

|

|

|

| A selection of "3-click" swing buttons: Links 386 Pro, Links LS 1998, and PGA Tour '96. | ||

|

|

|

| A selection of swing gauges from non-golf games: Relief Pitcher, Burnout Revenge, and Gears of War. | ||

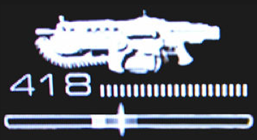

The swing gauge, really, is the most basic test of reflexes and timing in a video game. It appears in an awful lot of contexts besides golf. If ever there is a need to skill-check a player, without designing an entire user-interface paradigm or mini-game challenge for it, the humble swing gauge can handle it in a pinch. You'll easily see swing meters show up in games about other sports, like bowling, football, or even sometimes baseball, like Atari Games' Relief Pitcher. But some other games that use swing meters stretch the definition of sport. Revving up your engine for a good start off the line in Burnout Revenge? Three clicks and you're off. Prepping the galaxy's most earth-shattering punch in Kirby Super Star? A simple meter is but one of three swing gauges shown to you. Even the "tactical action horror" series, Gears of War, has a swing gauge that determines the speed with which your character reloads their weapon.

But swinging isn't always clicking. Incredible Technologies' long-running Golden Tee Golf series, a staple of sports bars since 1990, uses a large trackball. Players roll back the ball to begin the backswing, then thrust it forward to follow-through and strike the ball. There is a remarkable fuzziness to this movement; the straightness of the shot hinges entirely on the straightness by which the player moves the trackball. If a hook or a slice is desired, the player may choose to roll the ball forward at an angle, or if they have not quite gotten used to the trackball, they may do this by accident while trying to fling it as hard as possible. Later golf games for computer platforms, most notably Sierra's Front Page Sports Golf, Empire Interactive’s The Golf Pro, and Artdink's Big Honour, replicate a similar analog swing using a computer mouse.

| Front Page Sports Golf, 1997, Sierra On-Line, Windows. Demonstrating the flexibility of its mouse-movement-based TrueSwing system. (I will never tire of finding uses for this clip.) |

Video game consoles, too, sometimes take a unique path to simulate a golf swing. With the advent of analog joysticks in game controllers, golf games like EA Sports’ Tiger Woods PGA Tour and HB Studio’s The Golf Club use the innate elasticity of the thumbstick to stand in for the movement of the club, with intuitive back-then-forward movements and the inherent trickiness of trying to pull the stick back just enough to reach the desired power. Midway Games, seeking to replicate this in coin-ops, released an arcade machine in 1999 called Skins Game that featured a unique spring-loaded, pull-back joystick. Players would pull back the stick as far as desired, and slightly to the left or right to hook or slice the ball, and simply let go of it to swing.

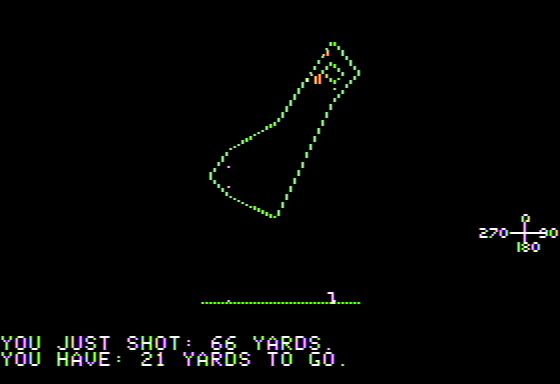

In even more extreme circumstances, on very early machines like DEC mainframes or the Apple II home computer, processing a moving swing meter was not even a thing; graphical routines were simply not advanced enough to have anything moving around in real-time. 1982’s Championship Golf, from Hayden Software, draws a crude outline of the current hole, a tiny white dot representing the location of the ball, and asks the player to manually type in a directional angle (in degrees, with a helpful on-screen guide to help players to identify which number represents “north”) and the power level of their swing (from 0 to 10). It is almost more of a math lesson than a golf game, though I confess, my math lessons rarely got as entertaining as this.

|

| Championship Golf, 1982, Hayden Software, Apple II. Shots are made by manually entering numbers for your chosen club, angle, and swing power with the keyboard. Screenshot by MobyGames contributor hoeksmas. |

Simulating a golf swing in these ways has a conceptual problem that is somewhat of a two-way street. Much of the game balance in a golf simulator lies not in the construction of the course itself, but in how difficult it is to swing with accuracy. To that end, many golf sims simplify swinging to a significant degree, allowing the player to directly set the ball spin, or the perfect amount of loft and curve, without even having to think about stance. On the other hand, many more detailed simulations like Links or T&E Soft’s True Golf Classics series offer a series of sliders to alter the placement of the golfer’s feet and the angle of the club head. This offers a degree of conscious mathematical thought to the player that, to a real professional golfer, is probably a matter of intuition and instinct more than it is of precise angles and carefully measured distances. It is not always immediately obvious to new players how these functions affect the ball’s path, either; it is entirely possible for the golfer to miss the ball if the sliders are set incorrectly. But this is, of course, assuming that a player even needs to engage with the menu at all; leaving the stance at its default setting will - more often than not - leave the player’s golfer already in the perfect position to hit the ball straight and true.

|

| Microsoft Golf 3.0, 1996, Microsoft, Windows. The Advanced Shot Setup window gives you unwise amounts of fine control over four distinct factors of your shot, from the distance between the golfer's feet, to the angle of the club face. |

Calculation, reflexes, muscle precision - things that, in real golf, must all work in concert to perform the perfect swing. Developers of golf sims may opt to replace mathematical precision and intensive muscle training with reflexive timing, requiring a different skill set to play well. There’s a lot for a developer of a golf game to think about, when it comes to simulating such a complicated movement. I am not sure we've even begun to capture every detail of it, but at the same time, I'm not sure that we need to. I feel that there are still unique ways yet to express the golf swing as a video game mechanic. And while they don't always make perfect physical sense, they can sometimes result in a golf game with a more fantastical appeal. Who says, for example, that you need to be swinging a club at the ball to make it fly?

|

| Nice Shot! The Gun Golfing Game, 2018, PolyGryph Studios, Windows. Shot spin and power are chosen by equipping larger and smaller caliber guns, and aiming the crosshair at different parts of the oversized ball. (I wish this game had committed harder to its premise.) |